Stop me if you’ve heard this one:

In 1985, Nintendo releases a game called Super Mario Bros. that completely revitalizes the flagging fortunes of the game industry, and it instantly becomes synonymous with their brand. Naturally, a sequel is out within a year: Super Mario Bros. 2, a kind of extra-difficult level pack running in the original game engine.

The only problem is, Nintendo feels like this new game is too difficult for the plodding, feeble-minded likes of their Western audience, and they refuse to release the game outside of Japan. This doesn’t become an issue until 1998, when the marketing juggernaught that is Super Mario Bros. 3 begins making itself known. Obviously, the Western audience needs some kind of “Mario 2” to fill in that gap, right? What’s a corporation to do?!

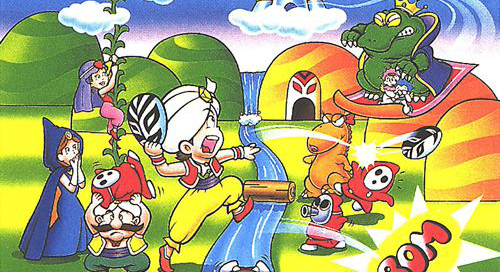

In this moment of desperation, Nintendo gropes around in its back catalog and comes back out with a quirky Japan-only gem called Doki Doki Panic. They proceed to shamelessly slap the Mario license onto Panic and shove it out the door to fend for itself in North America, doing little to cover up the drastic shift in gameplay mechanics and the bizarre new cast of enemies.

The neglected SMB2 would only ever be released in the West much later as part of the Super Mario Bros. All-Stars compilation for the SNES, under the title Super Mario Bros. – The Lost Levels Until then, we were stuck playing Doki Doki Panic, made hapless patsies by Nintendo’s devilish bait-and-switch! Shame, Nintendo! The light of pop culture history condemns you!!

I’m none too keen on this version of events. It’s catchy and it’s dramatic, but as we’ve seen in the case of Pokemon Green, the truth behind these weird localization snags is often weirder, more convoluted, and (I think) more interesting than it initially seems.

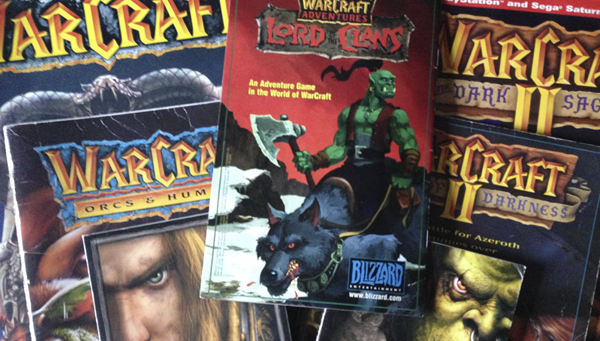

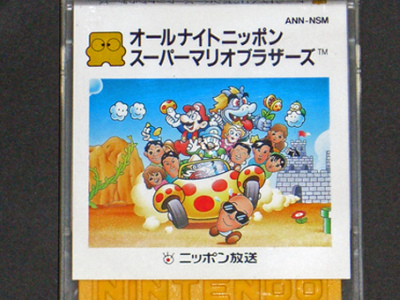

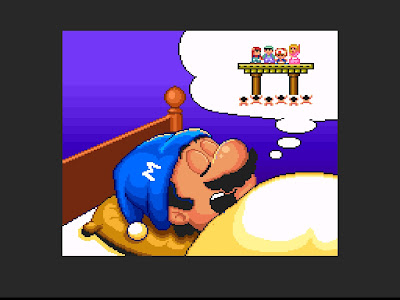

So firstly – Super Mario Bros. 2 is not really a unique game. I don’t mean this as a value judgment on the game’s originality (although, yeah, it’s basically an early form of a Kaizo hack, with stunning innovations like “maybe the squids are on land in this one?!”). There were actually other Japan-only “expansions” for Super Mario Bros., for instance the ultra-difficult Arcade version Vs. Super Mario Bros.. There was also the exquisitely bizarre All Night Nippon Super Mario Bros., featured above, a promotional tie-in with a popular radio station that swapped out stage enemies with pixelated idols and DJs. These games all came out in ’85 and ’86. Essentially, these were just extensions of the original Super Mario Bros. They represent Nintendo wringing all money they can from an existing chunk of technology before moving on to something new.

Secondly – if you compare the credits of Doki Doki Panic to those of Super Mario Bros. 2, you are going to see almost the exact same list of names. Like, almost to a man. As a matter of fact, the only big name on Doki Doki Panic that you wouldn’t recognize from the typical Mario crew is that of Kensuke Tanabe… but, hey, he was the game’s director, and evidently Doki was his brainchild. Hmm, I wonder where he came up with all these crazy, left-field ideas that would later be so carelessly repackaged as part of the Mario series…

Oh, right! He made them for a prototype of Super Mario Bros. 2. WHAT.

Tanabe’s Mario prototype was a cooperative vertically scrolling platformer, sort of like Ice Climber. The famous throwing mechanic was intended to allow players to build ladders and stairs to upper levels using objects from the environment. Miyamoto thought it needed more work, so it got put on the back burner and retooled to be a little more like the established side-scrolling formula.

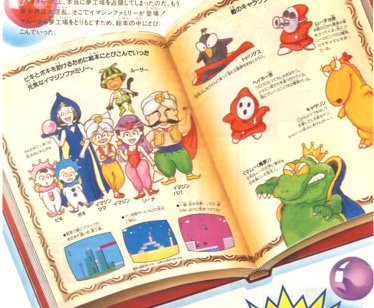

Around the same time, Fuji TV was partnering with Nintendo for a media expo called Yume Kōjō. Tanabe was handed a set of Arabian Nights lookin’ mascot dudes and told to make a promo game about them. So he killed two Dokis with one Panic and shamelessly slapped this new brand over top of his new Mario game!

It’s hard to say how much the rebranding actually changed the nascent Panic‘s development. It’s pretty likely we would never have had Toad and the Princess in our SMB2 had Tanabe not been handed a sheet of four characters. The floating move the Princess was originally supposed to be a flying carpet, and there’s a certain storybook aesthetic that remained a part of the game. But the gameplay, and every single character apart from the four principles, were all Mario team originals that very well may have been intended to be part of the Mario series.

So if Doki Doki Panic easily has enough Mario-cred to rival the true Super Mario Bros. 2, why does it seem like the black sheep of the family?

I think it’s important to remember that before Super Mario Bros., the Mario character had been known primarily for dodging giant apes and punching large crabs. Nobody had any idea what the next game in a projected “Mario series” was going to look like! Super Mario Bros. 2 represented a hewing to what was already popular, and Super Mario Bros. 3 finally calcified that formula into a recognizable franchise. Doki Doki Panic represents the very short window during which the series could have gone in any number of directions – and there’s something kind of cool about that.

Today, most of the cast of Doki Doki Panic has migrated over to the main dynasty of Mario Bros. games, and – as the four-character setup of Super Mario 3D World demonstrates – Nintendo is still in the debt of Tanabe’s wacky prototype. Doki might always be the frayed, incoherent uncle of the family, but it’s good to know that it still has a place at the table.

– CC